The Catholic Church did something revolutionary 45 years ago today. The world’s cardinals elected a Polish pope, who went on to change the world.

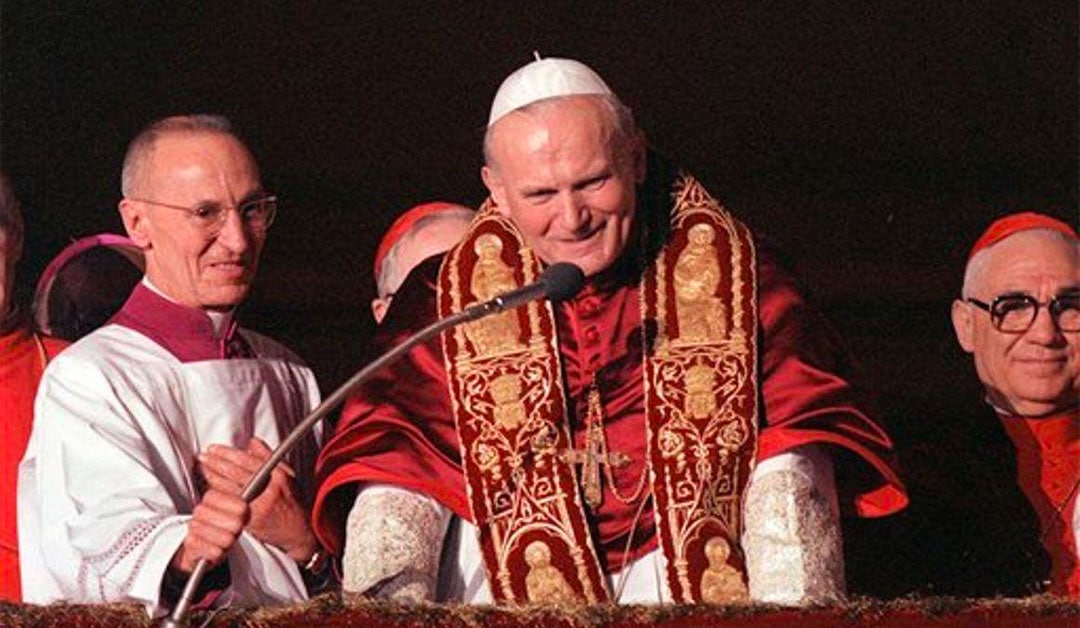

On the evening of October 16, 1978, when Cardinal Karol Wojtyła stepped out onto the loggia of Saint Peter’s Basilica for the first time as Pope John Paul II, he addressed the excited throng in perfect Italian.

Some were puzzled because they had learned from the introduction that he was not from Italy. They soon discovered that their new pontiff was fluent in nearly a dozen languages. In the 58-year-old pope’s unscripted remarks, he said, “I don’t know if I can explain myself well in your — in our — Italian language. If I make a mistake, you will correct me!”

At that moment, the first non-Italian pope in 455 years charmed the Italians and forever won their hearts. He would soon charm the world and begin a worldwide cascade of change inside and outside the Catholic Church.

A Series of Providential Events

Pope Saint John Paul II’s election was improbable for many reasons. The College of Cardinals had convened just two months earlier to elect Albino Luciani, who took the name Pope John Paul. He died just 33 days into his reign.

The cardinals’ choice of the first Slavic pope was also unlikely because Wojtyla came from the heart of Soviet-controlled Poland. To say that his election and unrelenting anti-communism enraged Moscow was an understatement.

Within a few years, according to scholar Paul Kengor, the Kremlin hatched a plot to eliminate John Paul II. They almost succeeded on May 13, 1981, when a professional assassin, Mehmet Ali Ağca, fired on the pope in St. Peter’s Square.

Surviving that tragic day allowed the young pope to forge an unlikely relationship with newly elected American President Ronald Reagan, who had survived an assassin’s bullet just months earlier.

Together, the Protestant president and Catholic pope set out to dismantle the Soviet Union.

A Witness to War and Tyranny

John Paul was perhaps more aware of the devastation caused by the 20th century’s flawed ideologies than any other world leader of his era. As a young man, he witnessed his beloved country overrun by Hitler’s Nazi regime. Years later, at the end of the Second World War, the Allies surrendered Poland to Moscow’s atheistic communists.

Young Karol Wojtyla experienced firsthand man’s inhumanity to man during one of the most brutal eras of the 20th century. While he was studying for the priesthood, Nazis regularly rounded up and executed priests and seminarians. During his priesthood, the Communists were equally brutal — particularly to people of faith.

“Not only did the people reject Nazism as a system aimed at the destruction of Poland and communism as an oppressive system imposed from the East, but in the process of resistance, they also pursued highly positive ideals,” John Paul wrote in his 2005 book Memory and Identity.

Those ideals were key to communism’s collapse in Eastern Europe. The first significant crack in the Iron Curtain began with John Paul’s nine-day visit to his native Poland in 1979. He arrived with tremendous hope for his nation, inspiring his countrymen to turn to God and to fight for their right to freedom.

John Paul II and Ronald Reagan: Kindred Spirits

That unprecedented visit had a tremendous impact on Reagan, who recorded several nationally syndicated radio broadcasts on the pope’s impact in Poland. “It has been a long time since we’ve seen a leader of such courage and such uncompromising dedication to simple morality — to the belief that right does make might,” Reagan said. The future U.S. president had found a kindred spirit in John Paul, someone willing to speak out against evil.

So how did the pope and the president bring an end to the “Evil Empire”? They had the temperament, the timing, the positions of power, and some help — divine and otherwise.

The Soviet empire was crumbling from within. Its economy was weak for many reasons, not the least of which was that the Soviets were trying to keep up with the United States in the arms race. Most importantly, however, Reagan and John Paul were utterly convinced that they were on the right side of history.

“The years ahead are great ones for this country, for the cause of freedom and the spread of civilization,” Reagan said in 1981. “The West won’t contain communism; it will transcend communism. It won’t bother to dismiss or denounce it; it will dismiss it as some bizarre chapter in human history whose last pages are even now being written.”

Ronald Reagan often referred to John Paul II as his ‘best friend’

John Paul and Reagan met several times, and the governments they led shared a tremendous amount of intelligence concerning Poland and the Soviet Union. Envoys regularly shuttled back and forth between Rome and Washington.

Declaring Spiritual War

Both world leaders supported the Polish Solidarity movement and railed against atheistic communism. However, both men knew this was far more a spiritual battle than a political one.

“Certainly, the curtailment of the religious freedom of individuals and communities is not only a painful experience, but it is above all an attack on man’s very dignity, independently of the religion professed or of the concept of the world which these individuals and communities have,” the pope wrote in 1979.

As Moscow clamped down on Poles, declaring martial law in 1981, John Paul and Reagan intensified support for Solidarity and their behind-the-scenes political maneuvering.

When Freedom Came Roaring Back

In June 1989, when Poland held free and open elections for the first time under communism, the stage was set for dramatic political change. Five months later, the Berlin Wall fell and, along with it, Eastern European communism.

The Cold War was over because of the courage of an American president and a group of cardinals in Rome who took a gamble on a charismatic young cardinal from Poland.

Patrick Novecosky is a Virginia-based journalist, author, international speaker, and pro-life activist. He met Pope St. John Paul II five times. His latest book is 100 Ways John Paul II Changed the World.

This article originally appeared at The Stream on October 16, 2023.