If Ireland’s patron saint were to peek out from his grave on March 17, he would be dumbfounded by the celebrations and shenanigans that take place around the world in his honor.

It’s a safe bet that St. Patrick never downed a green beer, dressed like a leprechaun, ate corned beef and cabbage, or saw a river dyed green.

When I was five years old and learned about St. Patrick, I decided to visit his grave in Northern Ireland one day. I made good on that promise 50 years later when I traveled to the small town of Downpatrick last fall.

Although he’s one of the world’s best-known saints, there’s a tremendous amount of mystery surrounding the man who reputedly drove out snakes and converted pagan Ireland.

What we do know about him is fascinating.

First of all, Patrick wasn’t even Irish. He was born at the end of Roman rule in Britain (late 300s) in either England or Scotland. He is believed to have died on March 17, around 460 A.D., which is traditionally the feast day of Catholic saints.

From Prisoner to Priest

Although Patrick’s father was a Catholic deacon, historians believe that he took on the role for tax incentives. As a result, young Patrick was not raised in a devout Christian home.

Patrick Novecosky visits St. Patrick’s Grave in Downpatrick, Northern Ireland, on Oct. 31, 2023.

When he was 16, Patrick was taken prisoner by a group of Irish raiders who attacked his family’s estate. They transported him to Ireland, where he spent six years in captivity — likely in County Antrim or County Mayo.

During his time as a slave, Patrick worked as a shepherd. Lonely and afraid, the young man turned to God for solace, becoming more devout in his Christian faith — and he began to dream of converting the Irish people to Christianity.

In his autobiography, Confession of Saint Patrick, he writes that a voice—which he believed to be God’s—spoke to him in a dream, telling him to leave Ireland.

The escape was relatively easy, but the journey was excruciating. Patrick walked from County Mayo to the Irish coast, then he hitched a ride back to Britain and walked hundreds of miles to his family’s home. There, Patrick writes that he experienced a second revelation—an angel in a dream tells him to return to Ireland as a missionary. Patrick soon began his seminary education, which lasted more than 15 years.

After his priestly ordination, his bishop sent him back to Ireland with a dual mission — to minister to Christians on the island and to begin to convert the Irish. According to tradition dating from the early Middle Ages, Patrick was the first bishop of Armagh and Primate of Ireland. He is credited with the rapid spread of Christianity in Ireland and converting a pagan society in the process.

Snakes and Shamrocks

The shamrock—often called the “seamroy” by the Celts—was considered a sacred plant in ancient Ireland because it symbolized the rebirth of spring. By the 17th century, it had become a symbol of emerging Irish nationalism.

According to legend, Patrick taught the Irish about the doctrine of the Holy Trinity by showing them the three-leafed plant, using it to describe the Christian teaching of three persons in one God. However, the earliest historical association of Patrick and the shamrock dates to the 1680s, 12 centuries after the saint’s death.

Another common St. Patrick story is that he banished snakes from the Emerald Isle. While it’s true that Ireland is a land without snakes, there’s little evidence to credit Patrick for driving them out. The earliest writings about Patrick and snakes are by Jocelyn of Furness, who lived in the late 12th century. He writes that Patrick chased them into the sea after they attacked him during his fast on a mountain.

Spreading the Faith

Patrick is best known for converting Ireland’s pagans to Christ. Familiar with the Irish language and culture, he incorporated traditional rituals into his lessons on Christianity instead of attempting to eradicate native Irish beliefs. He used bonfires to celebrate Easter since the Irish were used to honoring their gods with fire. He superimposed a sun, a well-known Irish symbol, onto the Christian cross. The result is what we now know as the Celtic cross.

When Patrick arrived, few Christians were on the island, and most Irish practiced a nature-based pagan religion. The culture centered on a rich tradition of oral legend and myth, so it’s no surprise that Patrick’s life story became distorted over the centuries. Creating dramatic tales as a way to remember history has long been a part of Ireland’s past.

Interestingly, Ireland’s patron — and mine — was never formally canonized by the Catholic Church. During the first thousand years of Christianity, there was no formal canonization process. After becoming a priest and helping to spread Christianity throughout the island, Patrick likely became a saint by popular acclaim.

That acclaim has spread near and far. Although I claim no Irish ancestry, I’ve always felt a strong kinship with St. Patrick and the Irish people. That kinship grew even stronger when I visited St. Patrick’s tomb last November. It was a bucket list trip worth every penny!

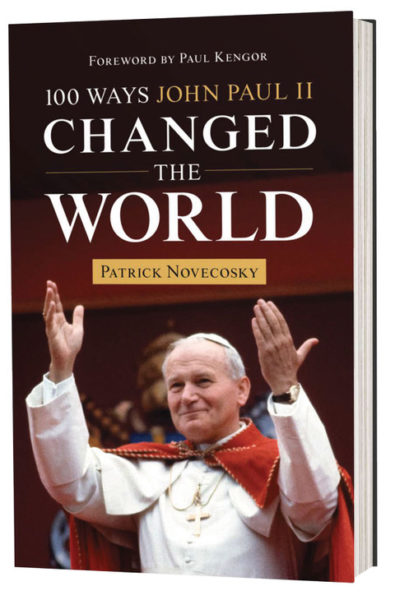

Patrick Novecosky is an author, international speaker and pro-life activist who met Pope St. John Paul II five times. His latest book is “100 Ways John Paul II Changed the World.” This article appeared in the March issue of Brookside Neighbors magazine in Warrenton, Virginia.