MY FAITH & FAMILY: Immaculée Ilibagiza shares the power of prayer — even in the darkest of places

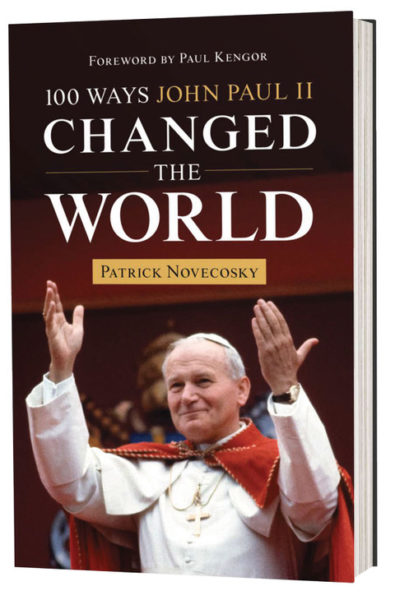

by Patrick Novecosky

The cultural distance between rural Rwanda and Midtown Manhattan is almost as wide as the Grand Canyon. But Immaculée Ilibagiza has walked the line between her African roots and her new life in America with grace and passion, sustained by her devotion to the Mother of God.

The cultural distance between rural Rwanda and Midtown Manhattan is almost as wide as the Grand Canyon. But Immaculée Ilibagiza has walked the line between her African roots and her new life in America with grace and passion, sustained by her devotion to the Mother of God.

“My faith was everything,” she says, recalling her miraculous survival during the 1994 Rwandan genocide. “I wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for my Catholic faith.”

A sought-after public speaker and New York Times best-selling author, Immaculée spent more than three months crammed into a small bathroom with seven other women during the genocide that claimed the lives of nearly 1 million people, including her parents and two brothers. She credits her parents’ faith and prayers not only for her survival, but also for her own faith, which sustained her during the ordeal.

“I grew up praying all the time,” she says. “My family prayed in front of the cross on our knees every night before we went to sleep. I remember the first step that brought me closer to God. It was in the fourth grade. My teacher read us the story of Our Lady of Fatima. I was struggling with whether faith was real and questioning so many things, but when she read that, it was like something convinced me that our faith is real.”

Immaculée’s father had a profound influence on her and their entire village. A Protestant convert to Catholicism, she says his sacrificial love and ardent prayer life helped form her love for the Church.

“My dad was the director of Catholic schools, and he gave all he had. That was his way. There was not one night that my family didn’t pray together. We prayed the Rosary and a number of other prayers — the Act of Faith, St. Michael, Hail Mary, Our Father. We went to church together and fasted together during Lent.

“Sunday was a day to dress up and go to church,” she explains. “No more work. It was a time to invite people to have dinner together. It was almost like a holy day every Sunday, and we always wore our best clothes, our best shoes.”

When Immaculée was finishing primary school, she nearly missed the opportunity to go to high school, which was only possible through a government scholarship. She was a good student, but because she was a Tutsi, the ruling Hutus kept her from advancement.

“It was a great sadness for my whole family for me not to have a scholarship,” she says. “My parents had to send me to a private school, and it was really expensive. They had to sell cows and land to get me there.”

Two years into high school, she had to take another exam to get into a better high school with government sponsorship. When she passed, her father threw a huge party, leaving Immaculée mystified.

“I said to him, ‘What is this? I know school is my future, but it’s not that important.’ He said, ‘You don’t understand. For two years I said the Rosary every single day for this intention — all the mysteries.’ So, not only did I get the scholarship, but I got into the exact school that my father had begged God to send me to.

“It was a shock for me. I wondered how God could answer such specific prayers. From that moment, I started saying the Rosary every morning. I went to bed with rosary beads in my hand. I woke up saying the Rosary, I slept saying it, asking God to help me pass my exams, to help me be good, to have a future.”

But while she was home from college on Easter break in 1994, life took an unexpected turn for Immaculée and her family. The assassination of Rwanda’s president ignited tensions between Tutsis and Hutus, sparking the genocide.

Just before Immaculée was rushed off to hide in a pastor’s bathroom, her father pulled out his rosary. “When we were separated during the genocide, he gave me a rosary,” she says. “That was the last gift he ever gave me. Even in his last moments, he asked people to pray. He said if this is from the government, we cannot stop it. It’s a chance to prepare ourselves to meet God and go to heaven.”

After tensions cooled, Immaculée was able to leave the country. She eventually found work with the United Nations, which brought her to the U.S. where she penned her first book, Left to Tell; Discovering God Amidst the Rwandan Holocaust. It has since been published in 15 languages. A full-length Hollywood film about her experience is also in the works.

In 2008, Immaculée wrote a follow-up book, Led by Faith: Rising from the Ashes of the Rwandan Genocide, and a book about Our Lady of Kibeho, the first Vatican-approved Marian apparition in Africa. Her Left to Tell Charitable Fund provides support for orphans in Rwanda.

Now, Immaculée and her family, including her daughter Nikki (11) and son Bryan (8), live in the heart of New York City.

“I used to feel like I would not get married and have children because I didn’t want to suffer if something bad should happen to them. I used to be worried all the time like my mother,” she explains. “Slowly, I have grown to understand that they are God’s children and he put them in my hands, to love them and not be scared about what could happen.

“Having children of my own has made me realize the purity of God’s love. If he loves me better than I love my own children, how can that be!? Jesus said you don’t give your children stones when they ask for bread. How much more does God love us! He gives us so much more.”

Despite the cultural chasm between her upbringing in Africa and the challenge of raising children in New York, Immaculée says her children already grasp the fundamentals of the Catholic faith.

“Many times they play Our Lady and Juan Diego. I’ll find my daughter standing on the table and she’ll have something on her head and she’s opening her arms and saying, ‘My son, Juan Diego!’ He had something he wrapped around his shoulders, and he says, ‘My Lady! My Queen!’”

Immaculée says she’s big on incorporating the Catholic faith into all aspects of their daily lives. She says she has the kids on a “program” that includes books, prayer and even children’s videos on the lives of the saints.

“People ask me how I teach the faith to my children. You get them where they can understand. I have cartoons of Fatima and Lourdes and they show their friends,” she says. “One time I told Nikki to be nice, and she said, ‘Mommy do you want me to be nice like St. Faustina? In the Divine Mercy video she always acts so lovingly.’ God is working through them.

“Of course they say their prayers, and I remind them that when they go to school and I’m not there, and somebody does something mean, call upon your Mother who is with you everywhere. I want to make her as real to them as my parents made her real to me.”

That kind of solid faith formation is vital to raising children in wealthy nation where materialism has become the norm, Immaculée says.

“The biggest difference could be not that America is so wealthy, but it’s that there are so many things available that are attractive to them and you can’t be there every second,” she explains. “The worst thing is TV and the Internet. You don’t know what a child can see on TV when you’re changing channels. Children are so exposed to things that are really for mature people.

“Pain and poverty has a way of teaching people to be more mature and appreciative. We don’t have what you call depression or stress in Rwanda. When I was there, I never felt stress like I do here. In Rwanda, you don’t have 20 things — including things that are good, fun things — pulling you in 20 directions. When you go home there are no movie theaters or TV. You meet your uncle or friends and have a conversation. You learn to appreciate people more for who they are rather than for what they have.”

Immaculée still has strong ties to Rwanda. In fact, she and her brother just finished rebuilding their parents’ home in Mataba, Rwanda. Ever since she published her first book, tourists from around the world have visited the place where she hid during the genocide. She says her parents’ home will now welcome those visitors and teach the importance of faith and family.

“I think it’s something that would have made my father proud,” she says. “We dedicated it to Our Lady of Kibeho, so it’s going to be like a museum to tell good news.

“Donations will help the village. My father wanted the village to have progress. This way, maybe his dream can come true. He wanted to help the sick, take them to the hospital, and build homes for those who didn’t have one.

“The whole village came out for the dedication, so I spoke to them. I said, ‘I have forgiven you, and I hope this home will be a symbol of love and forgiveness, a symbol of victory over hatred. In the end love will conquer. I hope this home will be a place where people can talk to each other.’”

Patrick Novecosky is the editor and founder of The Praetorium. This article was published in the Spring 2011 issue of Faith and Family magazine.

Patrick Novecosky with Immaculée Ilibagiza

From the article: “You learn to appreciate people more for who they are rather than for what they have.” Very important statement. Erich Fromm, Psychologist, wrote the book: To Have or To Be. It is about this concept. Mrs. Ilibigiza has a keen insight. She has a great story to tell, and I enjoyed reading about it here. It is a beautiful story of her ability to rise above the brutality and find peace enough to encourage others to love and respect each other in our human condition. Patrick has done a nice job of giving us a sense of… Read more »

A truly inspiring story.

Great article Patrick. I loved how she talked about not having depression and anxiety in Rwanda. I always wonder what our cross is in America. She is so inspiring. It is amazing to here her perspective! Thank you for the article. I shared it on my page.