For those of us who grew up in the wake of the Second Vatican Council — the era of felt banners and guitar Masses — the confusion over what the Catholic Church taught was real.

The catechesis of the 1970s became a cautionary tale, a model for what not to do when passing on the faith.

Our well-meaning teachers told us that “all you need is love,” echoing the Fab Four instead of reaching for the Baltimore Catechism. In 1978, they joked that after Pope John Paul I, we just might get Pope George Ringo.

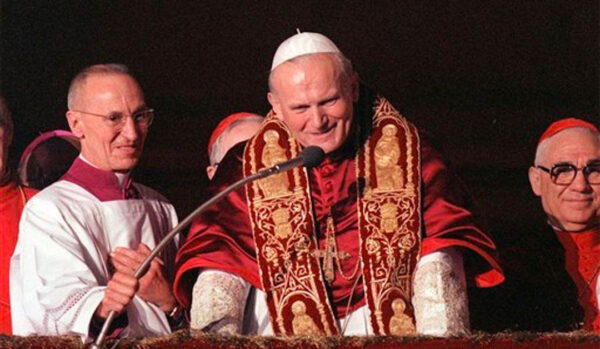

Instead, we got John Paul II.

Instead, we got John Paul II.

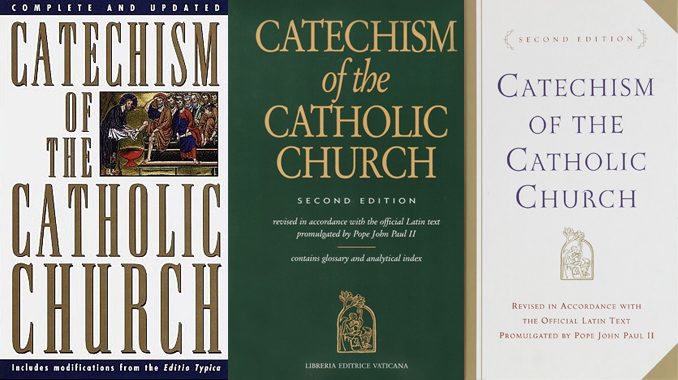

One of the Polish pontiff’s seminal accomplishments was to give us the Catechism of the Catholic Church. The English-language version dropped 30 years ago this week.

The Catechism was an instant international best-seller that became a reality only with the intervention of an American businessman. More on that in a moment.

John Paul II inherited the arduous task of unpacking Vatican II, arguably the most important religious event of the 20th century. The Council met in four sessions between 1962 and 1965. Pope St. John XXIII, who opened the Church’s 21st ecumenical council, asked bishops to examine how the Church could best proclaim the Gospel in the modern era.

Twenty years later, in 1985, John Paul convoked a meeting of bishops to examine how well the Church had implemented the Council. The synod returned with several recommendations, including the suggestion that the Church produce a new, comprehensive universal catechism.

Critics harped that the Church didn’t need a new Catechism. Papal biographer George Weigel has noted that opponents of the proposal said that Catholics were no longer interested in “conceptual” approaches to religious education.

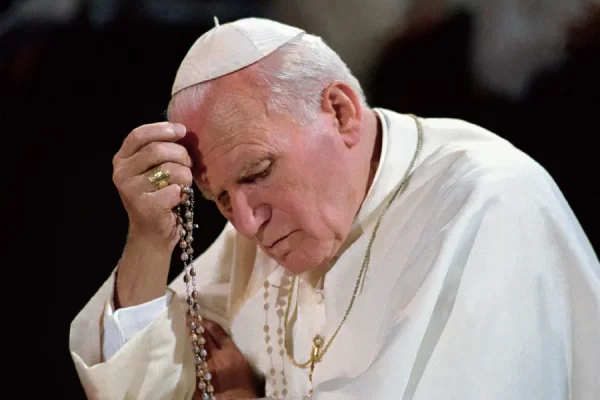

John Paul II persevered.

John Paul II persevered.

On May 27, 1994, the pope received the first English-language version of the Catechism. Even though nearly 700,000 copies of that version were on shelves by the end of June, the pope had no idea that he had an international bestseller on his hands.

Since its 1992 publication in French, the Catechism has sold about 20 million copies in at least 44 languages. It is the first comprehensive document to explain Catholic faith and morals in more than 400 years.

Following the Council of Trent (1545–1563), called in response to the Protestant Reformation, the Vatican published the Roman Catechism in 1566; council fathers found it necessary because both priests and the lay faithful at the time were poorly catechized.

John Paul II saw a parallel after the Second Vatican Council.

Decades of poor catechesis and the disastrous “Spirit of Vatican II” had the Catholic Church in turmoil. In developing a new universal catechism, John Paul II didn’t primarily intend to squash dissent. Instead, he wanted to put forth a modern, comprehensive, and authoritative teaching document containing all the tenets of the Catholic faith contained in Scripture and Tradition.

He tasked a group of 12 bishops with creating the new catechism. They were led by Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger—the future Pope Benedict XVI, then prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith—and Fr. Christoph Schönborn, later archbishop of Vienna.

Like all major undertakings, there were hiccups.

One significant obstacle was funding. Tight budgets had virtually brought the Vatican’s ambitious project to a grinding halt. The project apparently found an unlikely savior in American pizza tycoon Tom Monaghan.

The Domino’s Pizza founder was on a pilgrimage to Rome in the late 1980s and met with Schönborn. Monaghan, who would sell Domino’s for $1 billion in 1999, told the Austrian priest that he would sponsor the research, travel, staff, and equipment necessary to complete the project. In 2003, Schönborn acknowledged that without Monaghan, the Catechism might never have been published.

Politically correct opposition demanded gender-neutral language. But the English-language version retained the generic use of “man” and “men” for humanity, both men and women.

John Paul II also drew fire for the Catechism’s stance on the death penalty after later revisions. The Catechism’s first edition discouraged authorities from capital punishment. In 1997, John Paul ordered an update of paragraph 2267 limiting the use of the death penalty to circumstances where it was the “only possible way of effectively defending human lives against the unjust aggressor.”

That revision was drawn from his 1994 encyclical Evangelium Vitae, in which he wrote that “as a result of steady improvements in the organization of the penal system, such cases are very rare, if not practically non-existent.”

In 1999, John Paul told Catholics in St. Louis that “modern society has the means of protecting itself without definitively denying criminals the chance to reform. I renew the appeal I made most recently at Christmas for a consensus to end the death penalty, which is both cruel and unnecessary.”

Twenty years later, Pope Francis revised the passage again. “The death penalty is inadmissible because it is an attack on the inviolability and dignity of the person, and the Catholic Church works with determination for its abolition worldwide.”

In its 30-year run, the Catechism has proven to be an indispensable resource for catechesis and evangelization. It spells out the “what” and “why” of Church teaching — and distinguishes the Catholic Church from other world religions.

After all, what other major faith has published a comprehensive volume of its beliefs and the reasons behind them?

Patrick Novecosky is a Virginia-based journalist, author, international speaker, and pro-life activist. He met Pope St. John Paul II five times. His latest book is 100 Ways John Paul II Changed the World.

This article first appeared at The Catholic World Report on May 29, 2024.